Unlike most successful CEOs, Lorenzo Gomez doesn’t have an MBA, or a famous pedigree, or any family connections to business.

In fact, he doesn’t even have a college degree.

But he does have a very unique story.

Lorenzo Gomez grew up in “the hood” of San Antonio, Texas. One of seven children, he came from the type of poverty that is typical for many families in South Texas.

When other future CEOs were spending their summers on golf courses or doing unpaid internships, he was bagging groceries at his local HEB—a Texas institution, especially for working-class hispanic families like Lorenzo’s.

As a teenager working at HEB, Lorenzo was so shy he even avoided small talk with the cashiers. When he could, Lorenzo steered clear of people altogether.

“Growing up for me was about hiding in plain sight. Don’t say anything stupid, don’t make eye contact, and never draw attention to myself. For the most part, my strategies worked, which completely stunted my personal development.”

As Lorenzo progressed through high school, he turned to a creative outlet—storytelling—as a way of gaining confidence in social situations. Telling stories about his neighborhood and the people around him gave him some control in uncomfortable interactions, rather than being a victim of his own anxieties.

After high school, instead of going to college, Lorenzo’s coworker at HEB helped him get a job at Rackspace, a cloud computing company. Working for a tech company was a potential disaster for Lorenzo: the IT field represented an opportunity for more social isolation.

But he didn’t want to live his life as a social outcast; he wanted a team. Rather than retreating further away from people, Lorenzo used his new job as an opportunity to become more comfortable interacting with people.

Lorenzo encountered challenges on his journey, and he wanted to share his stories in a book.

Whenever one of his coworkers at Rackspace had a tough day, or when Lorenzo could feel tension on the team, he’d stop everyone in the middle of their work, gather them around, and they’d tell stories.

Storytelling had been an important part of dealing with his own anxieties—Lorenzo wanted his teammates to feel the same benefits. The team took to Lorenzo’s style, really responding to how he used storytelling as an integral part of their culture.

A large part of this was not only because he was a good storyteller, but because of his uniquely challenging road to success, and because Lorenzo was always willing to be vulnerable about his mistakes along the way, as well as stories from his childhood in San Antonio.

Because of his ability to connect with people through story, Lorenzo eventually moved into a leadership position at Rackspace. Over time, Lorenzo reached the highest levels of management at Rackspace, then founded a philanthropic organization, became CEO of one of the largest coworking spaces in Texas (Geekdom), and co-founded a tech advocacy group.

Along the way, Lorenzo learned hard lessons about leadership, networking, and mentorship. Without an MBA, or even a college degree—and without mentors or successful people around him who had a similar past—he often felt his lessons were harder won than the business leaders around him, and were applicable to people who did not always fit the “conventional” mold of business success.

Lorenzo had dreamed of writing a book about his journey for years—he just never knew what to write it about.

He picked at his manuscript for more than a decade.

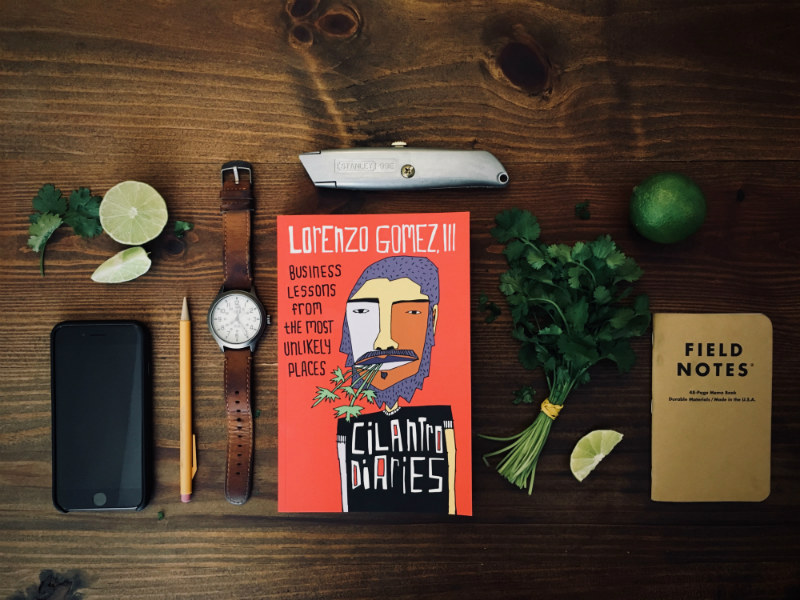

In moments of frustration at work, Lorenzo would open a file on his computer titled “Cilantro Diaries,” named after one of his stories as a bagger at HEB. He would type away for as long as it took to scratch his creative itch. Then he’d leave the file untouched until the next time he felt stressed.

He continued like that for more than ten years.

After a decade of frustration, Lorenzo had 70 pages of disjointed storytelling and three different tables of contents he’d developed.

Adding to his frustration was his lack of support. He didn’t know any writers, let alone any writers of color, or even anybody who had written about reaching success after growing up in the hood.

“Hemingway went to Paris and surrounded himself with other writers to improve his art. I was stuck in San Antonio, Texas. I definitely did not have an F. Scott Fitzgerald around me.”

Without a community of writers to encourage him, Lorenzo believed he wasn’t meant to write a book. To him, the idea of finishing his book was a joke.

“Whenever I mentioned my book idea, I’d say, ‘One day, when I write the book I’m never going to write…’ It was my way of coping with the fear that I’d never finish.”

Lorenzo discovered the help he needed to finish his book.

Luckily for Lorenzo, one of his friends heard him make that joke and challenged him to take the steps necessary to complete his book-writing journey. He sent Lorenzo a podcast interview with Scribe Media co-founder Tucker Max.

Lorenzo listened to the interview late one night as he sat in his office doing expense reports. On the podcast, Tucker explained the Scribe book-writing process as a team effort, with editors, proofreaders, publishing managers, and more helping people like Lorenzo share their stories with the world.

This was exactly what he needed. Suddenly, a decade of frustration had turned into a moment of anticipation—he might actually finish his book.

Lorenzo’s first conversation with a Scribe publishing manager brought back some old anxieties for him.

“One of the first things they said was, ‘Tell me a story.’ I loved that they had a strict screening process for their authors, but I was terrified he’d think my stories weren’t good enough for a book.”

His new publishing manager loved his stories, and Lorenzo dove headfirst into writing his book with Scribe.

Lorenzo found a new focus: helping young people like him.

Lorenzo entered the process full of hope: he would finally share his stories to the world outside of his business community.

Everyone knew that Lorenzo had great stories, but as he wrote the book he realized that unless he made every story relevant for his readers, it would only benefit one person: himself.

He imagined young Hispanic teenagers bagging groceries at HEBs across Texas—the same job he used to have. If he didn’t write his book with those kids in mind, who would they have to look up to as an example of business success?

Suddenly, he had his ideal reader in mind. No matter how entertaining a story was, if it didn’t help young people who grew up like him, Lorenzo left it out.

“It was painful to go through those 70 pages I’d written and realize they wouldn’t make it into the book. I’d spent 10 years writing stuff that nobody would read. It was painful, but liberating—I had a fresh focus: my reader.”

Lorenzo looked forward to every weekly call. It was a joy for him to recharge creatively. But he wasn’t only creating for his own sake. It took him a long time to see it, but Lorenzo was writing the book he wished his younger self could have read.

With his newfound focus and determination, Lorenzo finished his book in a matter of months.

Lorenzo now gives speeches to high schools and colleges across Texas.

When Lorenzo got his first advance copy of The Cilantro Diaries, he teared up at the sight of it. Immediately, he rushed over to Momma Gomez’s house to share it with her. His mom loved his stories and the cover design so much, she asked if she could keep it.

“That moment changed the script in my head. My book wasn’t a joke anymore—it was complete, and it was something that people from my neighborhood would want.”

Lorenzo never predicted the ownership other people would feel with his book. He did not realize it at the time, but there were virtually no hispanic CEOs who wrote books, and none that wrote them in an engaging way that resonated with younger kids from working class families.

Because of this—because of his unique perspective that resonated so deeply with his community—the book took off.

Every month, Lorenzo gets emails from schools and other organizations asking him to speak about his book. He received a call from one teacher who wanted to buy a copy of his book for every single student in her high school.

The students had never read a business book from someone like Lorenzo: a man who could have been their older brother, who came out of a hispanic working-class neighborhood like theirs, and made it out to become a successful CEO.

Lorenzo thought it couldn’t get any better than that.

He was wrong. A professor at Texas A&M read The Cilantro Diaries, and before he’d even finished the book, he called Lorenzo. The professor wanted to purchase 300 copies and make the book required reading for his university students.

And he wanted Lorenzo to keynote a symposium for him.

“I thought I was dreaming, but the dream just keeps going. It’s humbling and, frankly, pretty scary that so many people are putting their reputation on the line so that other people will get to hear about my book.”

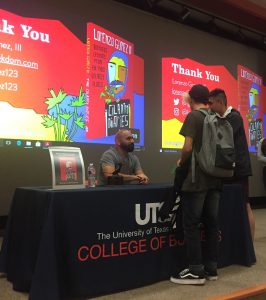

Just weeks after publication, the University of Texas at San Antonio, which is predominantly hispanic, contacted Lorenzo to talk to their students about his book.

After his talk, the business school professors told Lorenzo he was their first speaker who had students approaching him offstage after his speech. They wanted to get Lorenzo in front of a wider audience.

UTSA asked him to be the commencement speaker for their Spring 2018 graduating class at the Alamodome.

“If I had known someone would ask me to give a commencement speech, I would have never written a book in the first place. I was terrified, and I’m still terrified just thinking about it, but it was one of the most gratifying moments of my life.”

Lorenzo Gomez, who grew up bagging groceries at HEB, who never got a college degree, but still eventually became a CEO, stood in front of a 72,000-seat stadium and inspired thousands of Hispanic students just like him about to embark on their own professional journeys.

“If I never wrote my book, I would have felt the distinct absence of a creative outlet. It would be like not telling my best friend I loved him before he passed away. I still don’t have a college degree—and I’ll probably never get one—because I have something better: my book.”