The best way to write is the way you talk—at least for most writing.

It’s conversational, and it’s easy to read. That’s exactly what you want in a book.

The way we speak isn’t always grammatically correct, but that’s okay.

Grammar rules are arbitrary and completely made-up.

They’re only “rules” because certain people decided to make them “rules,” and those same people change them every year.

That’s why grammar books have so many different editions.

There are only 2 reasons to follow some generally accepted rules of grammar:

- They make communication easier

- People expect them (hence, communication is easier)

The only real point of following conventional grammar is to meet the expectations of your readers.

This post lays out the difference between the few grammar rules that matter and the vast majority that don’t.

When it’s okay to break the rules

Before I dive into the grammar mistakes you need to avoid, I’ll preface it by saying this: there are times when breaking “the rules” is okay.

In fact, there are tons of great books, including bestsellers, that break grammatical rules left and right.

How can they get away with it? Because readers don’t care—as long as it’s intentional and it works.

In fact, there are plenty of good reasons to ignore grammar rules:

- to be more conversational

- to reduce cognitive load

- to be true to your own voice

- to entertain the reader

- to tell a good story

But the best reason of all to ignore grammar is this one:

To get out of your own way and finish your draft.

Don’t worry about grammar when you’re writing. Leave that problem for editing.

Once your first draft is finished and you start editing your own work, you’ll want it to be as clean as possible before sending it to your editor.

But that doesn’t mean all the grammar needs to be “correct.”

You just want to fix the common mistakes that will make you look unprofessional.

Here’s the good news:

There aren’t many grammar errors you should bother to fix before sending your work to an editor.

I say this for 2 reasons:

- An editor doesn’t expect your work to be perfect. If it was, they wouldn’t have a job.

- For almost every kind of grammar “mistake,” I could show you a bestseller that uses it on purpose.

So, if you’re poring over English grammar books that extol the use of the semicolon and wail about the death of the English language, throw those out right now.

Why? Because many of those “grammatical errors” show up in good writing fairly often:

- sentence fragments

- run-on sentences

- split infinitives

- compound sentences that ignore commas

Instead, just follow this list of the most common grammatical errors, and know how to fix them.

Get these right, and then send that manuscript to your editor to do the rest.

10 Common Grammar Mistakes (and Writing Mistakes) to Avoid

1. They’re vs. their vs. there

Why isn’t it okay to break this “rule”?

Because it’s not really about grammar. It’s about spelling—and using the wrong word.

If you confuse these 3 words with each other, you might as well be using the word “bed” instead of the word “bad.”

They have completely different meanings.

So, which is which?

When to use they’re

They’re is a substitute (technically a contraction) for they are.

Use it whenever saying they are instead of they’re makes sense.

Example 1:

- “They’re going to the store.”

- They are going to the store? (That works!)

They’re is correct because you can substitute they are and the sentence still makes sense.

Example 2:

- “Put it over there.”

- Put it over they are? (Ugh, no.)

They’re doesn’t work. If you write out they are, the sentence doesn’t make sense.

Just remember: if they are works, you want they’re—the one with the y in it. Like they.

When to use their

Their is used when describing something that belongs to them. Technically, it’s a possessive pronoun.

Example:

- “Is that their sweater?”

- Is that they are sweater? (Ugh, no.)

- Does the sweater belong to them? (That works!)

When to use there

There is often about place. It looks just like where, but with a t.

Where? There.

- “Oh, that thing? Put it over there.”

- Where? There! (That works!)

There is also used in the expression there is.

- “There is a reason you need to pay attention to these 3 words.”

If you could just as easily say there’s, you want this word.

- “There’s a reason you need to …”

2. It’s vs. its

Similarly, it’s and its are two different words.

It’s is short for it is. If you can substitute it is and the sentence still makes sense, you want it’s.

Example 1:

- “It’s almost time.”

- It is almost time? (That works!)

It’s is correct because you can substitute it is and the sentence still works, even if it sounds a bit more formal.

Example 2:

- “Turn its wheel to the left.”

- Turn it is wheel to the left? (Ugh, no.)

This time, you need its, which expresses the idea of something belonging to something else.

- “Its wheel is the wheel that belongs to it.”

Just remember: only use it’s when you can substitute it is.

Otherwise, use its—because something belongs to it.

3. You’re vs. your

This one’s very similar. The one with the apostrophe is a contraction.

You’re is short for you are. If you can substitute the two words and the sentence still makes sense, you want you’re.

Example 1:

- “You’re right!”

- You are right? (That works!)

The sentence sounds more formal, but it still makes sense. You’re is the right word.

Example 2:

- “Is that your final answer?”

- Is that you are final answer? (Ugh, no.)

Here, you need the word your, which expresses the idea that something belongs to you.

Your final answer is yours, not someone else’s.

Just remember: if you can substitute you are and it still makes sense, you want you’re.

4. Affect vs. effect

This is another one where changing the spelling means you’re changing the meaning.

They’re both words; they just mean different things. But they’re somewhat related, so it’s tricky.

Here’s the most common way you’d use them both:

- “When you affect something, you have an effect on it.”

Here, affect is the verb. When you’re affecting something, you’re doing something.

Effect is the noun: an effect, or the effect, or effects.

- “It had a strange effect on me.”

- “We decided it was just an effect of the light.”

- “The special effects were phenomenal.”

This gets a little more complicated because you’ll occasionally see effect used as a verb, meaning “to bring about.” It’s most commonly used with nouns like “change” or “solutions.”

Similarly, affect can also be a noun, but it’s hardly ever used that way. It shows up mostly in psychology, to mean a feeling or emotion.

Unless you’re writing a psychology textbook, you can ignore that one and stick to this general rule:

Affect is the verb. Effect is the noun.

5. Principle vs. principal

This is the last example of words that sound the same but mean different things.

There are plenty of other words in the English language that suffer this kind of confusion, but if you get these first 5 right, you’ll look reasonably professional to an editor.

Principal is the adjective

- “What’s the principal lesson here?”

- “She was the CEO’s principal advisor.”

- “They will owe 15% of the principal amount.”

When the word means main or first or of money, you want principal.

Principal is also a person who runs a school or a company

- “The principal is your pal.”

You’ve probably heard that expression. It’s a common mnemonic for remembering this part of the rule.

The principal of a company is also your pal.

Principle is always a noun—it’s a truth or rule

- “The principle of gravity.”

- “The first principle of flight.”

- “Don’t ask me to go against my principles.”

- “Learn these 10 fundamental principles of grammar, and you’ll be in great shape.”

6. Using apostrophes

Apostrophes are used in contractions—squashing two words together

- “You’re right! You are!”

- “It’s true! It is!”

Apostrophes are NOT used to make things plural.

That’s one of the most common grammatical mistakes people make with apostrophes. Don’t do that.

- “One doughnut. Lots of doughnuts.” (NOT lots of doughnut’s.)

Possessive pronouns do NOT have apostrophes

- “His food is his.”

- “Her food is hers.”

- “Its food is its.”

- “Your food is yours.”

- “Their food is theirs.”

- “Our food is ours.”

DO use an apostrophe BEFORE the s to make a noun possessive:

- “The kid’s food belongs to the kid.”

- “The uncle’s food belongs to the uncle.”

- “The principal’s food belongs to the principal.”

Use an apostrophe AFTER the s to make a plural noun possessive:

- “The kids’ food belongs to the kids.” (It belongs to many kids, not just one.)

- “The uncles’ food belongs to the uncles.”

- “The principals’ food belongs to the principals.”

7. Hyphens vs. em dashes

Hyphens are used in hyphenated words. Obviously.

The detailed rules about hyphens vary from one manual to the next, and most of them aren’t worth the effort.

But there are a few basics that are worth paying attention to.

Use nothing if you have an -ly adverb and an adjective together

- “An unusually strong wind blew from the north.” (NOT unusually-strong.)

- “Her perfectly aimed shot split the arrow in two.” (NOT perfectly-aimed.)

Use a hyphen for adjectives that are two words together before a noun

- “A well-read student has read a lot of books.”

- “A high-stakes poker game has high stakes.”

Note that you DON’T hyphenate adjectives that come after the noun (usually).

If you’re not sure about a certain instance, don’t worry about it. Let your editor decide.

Use the longer em dash for breaks in a sentence, with no spaces

- “It was the first time I ever flew—the first time I experienced that freedom.”

8. Missing commas that change the meaning

The Chicago Manual of Style is getting a lot looser about commas these days.

But you still have to pay attention to them when they have the power to change your meaning.

Use a comma when addressing someone directly

Take a look at these:

- “Friends, don’t ever do that.”

- “Friends don’t ever do that.”

In the first one, you’re talking to the reader, addressing them as friends, telling them not to do something.

In the second, you’re making a statement about friendship.

The comma isn’t just a pause—it’s a clue to the reader that changes the entire sentence structure.

Use commas to separate items in lists

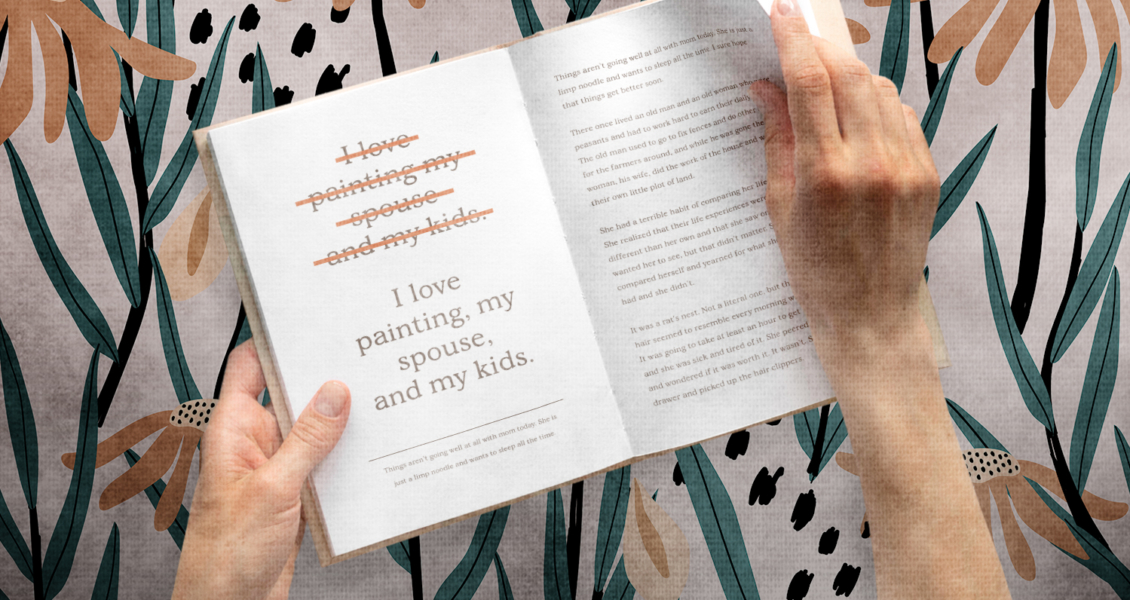

- “I love painting my spouse and my kids.”

- “I love painting, my spouse, and my kids.”

In the first one, the Author loves painting pictures of their spouse and kids.

In the second, the Author loves painting as an activity, and also loves their spouse and their kids.

If you’ve ever heard grammar lovers argue about the Oxford comma, it has to do with commas in lists.

And it’s the perfect example of the fact that the rules are made up.

The Oxford Guide (to British English), insists on using a comma before the “and” at the end of a list of things.

- “I love painting, my spouse, and my kids.”

The Chicago Manual (of American English) used to agree but eventually rebelled and said hey, if you don’t want to use that last comma, you don’t have to.

- “I love painting, my spouse and my kids.”

In that example, there’s not much difference. But in some lists, leaving that last comma out can make things less clear.

In the end, here’s the best rule to follow: do whatever will make the most sense for your readers.

9. Using quotation marks

Use quotation marks to indicate that someone is speaking, or when directly quoting someone or something.

- “Hector,” she asked, “have you seen my glasses?”

- “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times …”—Charles Dickens.

You can also use them to indicate sarcasm or tongue-in-cheek descriptions.

- Our first “security system” consisted of a tiny bell over the shop door and a Teacup Chihuahua named Spike.

10. Active voice vs. passive voice

This one isn’t technically a grammar issue. It’s just a key tip for good writing:

Be direct. Be active. Use simple words.

Here’s an example:

- “The factory was purchased by our team in the summer of 2007. By the following winter, it was ready for us to start up the lines.”

- “We purchased the factory in the summer of 2007. By the following winter, we were ready to start up the lines.”

- “We bought the factory in July, 2007. By December, we were cranking out our first product.”

The first example uses passive voice. The factory was bought by us—instead of just saying we bought the factory.

I see this kind of writing a lot when Authors are trying to sound smart.

Don’t do that. It’s not something you have to worry about.

Readers assume you’re smart. You wrote a book. Don’t make them work hard to read it.

The second example moves to active voice. It’s better, but it’s still using words like “purchased” and phrases like “the following winter.”

The third example is by far the easiest to read. It also has more personality, despite using smaller words.

And it’s much more engaging.

So don’t spend a ton of time worrying about independent clauses, dangling modifiers, and coordinating conjunctions.

That’s what editing and proofreading are for.

Instead, focus on crisp, clear, direct writing. That’s what really matters.